Q&A WITH DOUG ENG

December 28, 2021

BY MOCA STAFF

Curatorial Intern Skyler Dunbar met with artist Doug Eng to discuss his exhibition Nature of Structure | Structure of Nature, on view at MOCA through January 2, 2022.

Q: How did you decide which of your artworks would represent your career as a photographer in your retrospective exhibition Structure of Nature | Nature of Structure?

A: It was a big deal, you know, when curator Ylva Rouse told me she was interested in doing a retrospective, not just a standard exhibition. It really forces you to look back over the stuff you've done and closely examine it to consider whether it's significant. It makes you assess what it represents, and how you want to move forward in your work. So those were kind of the criteria I was using while making selections. And there was so much to sort through, because I've done a lot of public art projects, and I also just have so much work from the beginning of my career when I was still figuring everything out. And I always felt that if you're of service to someone or an organization, it's always easier to create because you have a goal or intention, but for this sort of exhibition you want something really personal, so it's hard. But this retrospective is a bit more recent and focused. I really try to think about the intersection of nature and our footprint on it. I think a lot of people are concerned about that right now and haven't fully begun addressing it yet.

I have a unique take on photography, I think it probably comes from my background. I was educated as an engineer and then I had a software business for a long time. I've got this analytical, structured way of looking at things as a result. I think it's pretty evident in how I photograph and represent the subject matter of my work. I try to be precise, not really abstract.

Q: Are there any particular people that come to mind when you think of artists of individuals who are making a difference through their art or advocacy?

A: There are a lot of photographers to credit. You can start back from the beginning, of course, with people like Ansel Adams. That's a name that everyone throws out but there are more contemporary photographers as well, like Robert Glenn Ketchum. There's a whole list I could give, but I have a teacher that I've taken a lot of workshops from. His name is John Paul Caponigro, and his father was Paul Caponigro, who's a fairly famous photographer. He really got me oriented towards the environment as my subject and respecting the environment through photography. Gosh, there's also Clyde Butcher, of course, and just so many others. A weakness of mine is buying books, so I can just pull books off my studio shelves any time and look at the work of so many different artists who are all inspirational. But there is certainly no shortage of other artists to find inspiration from.

Q: Can you elaborate on your artistic process and the message you convey through your photography?

A: My thing is trees. Well, it's nature, but it's specifically trees. If I have an idea or an opinion about something, I can usually communicate it through a representation of trees or the forest. Whether it's ideas about beauty, or feelings, or a concept of home or where I'm from, I can always relate it back to a feeling of being outside and being in nature. I went through a period where I studied the structure of trees, comparing them to buildings or the forest to an urban landscape. I shoot everything the same way, whether I'm shooting a building or a tree, I use the same lens. And I look for the same things, for continuity in the cityscape or the forest. And in the forest, you know, it all kind of looks the same. But I shoot in a lot of old growth forests, and they got me to start looking at the local landscape and its uniqueness. The Florida landscape is interesting, because people don't come to north Florida or Jacksonville for the natural landscape, but I was determined to find something in it. So, I just started shooting, taking these long panoramic images of the pine trees and putting them together until I found something interesting. And it worked, I was able to see something new and different in this landscape by changing the format we use to look at it. I tried to make it more sequential, so you don't just look at one tree but an entire setting, and those photos are present throughout the exhibition.

© Doug Eng, Tactile Wilderness, Hoh Rain Forest, Olympic National Park – Forks, WA, 2013. Inkjet print, 158 x 20 inches. Courtesy of the Artist.

I also thought how you experience a forest when you're walking through it is interesting. It's sort of like a wallpaper, as it keeps going and maybe changes a little but it's still kind of the same. I wanted to evoke that same sort of feeling, of course there's a difference when you're actually hiking but I wanted to show that visual experience by assembling these images and exploring the contrast and continuity and express how I felt walking through these old growth forests. I try to enhance the presentation of the image by changing the visual field in some way.

For example, varying the plane and way in which the images are mounted can show a new perspective and demonstrate that there's a lot to be revealed in these pine forests, there's a lot within this layering. And when the weather changes the environment changes. So, I like to examine the landscape and how it reveals itself at different times, like during a fog change. It can really give the photo a level of dimension. Suddenly, you can see something happening behind the trees, or a new layer appears depending on how you look at it. So, I like to experiment with different ways of mounting, different ways of displaying and presenting the photos.

Q: Could you elaborate a bit more on the message you wish to convey through Structure of Nature | Nature of Structure and what you hope viewers pay attention to?

I think we're just beginning to understand the environmental issues that plague us, especially at a local level. I know I'm still learning, and no one knows what's happening to our environment until it's mentioned on the news. And even then, no one really thinks about it after they first learn of it. That's certainly what happens here when hurricanes blow through, once the rain has passed we forget it ever happened. In February of 2019 my wife and I were driving to Alabama, and we were on the interstate just passing decimated areas of flattened trees and destroyed areas of forest. And it was so odd because it was so sudden, there was no lead up or warning, just, suddenly you're in the area that suffered the wrath of past hurricanes, this particular area was decimated in the autumn of 2018 by disasters like Hurricane Michael, and it's this absolute zone of destruction. It's only through this rough recollection of past news stories about the hurricane that you remember hearing about the danger of the hurricane, or maybe even hearing reports of the damage, but when you actually see it, it was just 15 or 20 miles of nothing. And then you're past it, and everything is normal again. It was so easy to forget until we drove back home and had to pass it again. And I came across this area in February of 2019, about six months after the damage had already been cleaned and the roads had been cleared, but most of the property where the damage occurred was still, it looked like it kind of just happened.

© Doug Eng, Leaning Forest, FL 71 – Kinard, FL, 2019. Inkjet print, 32 x 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

After that I made a conscious effort to document hurricane damage, to go find areas to photograph. It was a very self-aware process, because I was, pulling my car off the road, getting out, setting up my tripod, taking pictures of this damage, and people were going by and watching, and I was very conscious of it. It was almost uncomfortable, but it was really enlightening to see the damage and understand the real level of destruction. And I met a few people as a result of doing this, because I would just be out with my camera on dirt roads and someone would drive out and ask, you know, “hey, what are you doing here?” and I'd have to worry if I was accidentally trespassing or causing a disturbance. But I got to talk to people and hear their stories about the hurricanes coming through and realize what a massive deal it was for them.

The Eastern hemlocks was another area of damage and decimation that I got to document. The eradication of these trees all along the east coast due to an infestation of insects called hemlock woolly adelgids. Initially I didn't know what was going on, I just saw these dead, decaying trees and photographed them but later learned that the Eastern hemlocks were wiped out across the Smokies and Shenandoah area, where masses of old growth trees used to live. And there were millions of them, but these bugs infested the area and wreaked havoc, doing the most damage from 2008-2010. These 400-500-year-old trees would be killed in a couple of years. It was a horrifying story, and once I understood it, I could go up to the Blue Ridge Mountains and see the damage and understand it. Just, skeletons of trees are everywhere, and it made me much more aware of the importance of an informed perspective. And the bugs are still there, the people in the region are spraying the trees to try to fight the infestation but you can't fight an invasive species. Spraying every tree down with insecticide, you know, it takes time, and you might save a few trees, but you can't save the whole forest.

© Doug Eng, Approach to Blue Springs (from the Drowned Forest series), Ocklawaha River – Interlachen, FL, 2019. Wall vinyl, 147 x 18 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

An additional issue is the Rodman Reservoir on the Ocklawaha River here in northeast Florida. That reservoir is impounding the river right now, and the movement to take the dam down has been around since the sixties. The whole point of the reservoir is to create this barge canal across Florida, which requires raising the water levels or digging to deepen the river's floor. It's easiest to just choke off the river to increase water levels so that's what the state opted to do. And it's killed an entire floodplain that was covered in cypress trees, which were second generation trees because we had already gone through and cut down the original trees and cleared the area. But you could still see some old growth there, I mean, those original trees were unbelievable in size, just massive. I go to the reservoir every four years because they lower it to get rid of the vegetation that can cause clogs. Like flushing the toilet and bringing the water down. It exposes this drowned landscape, and it's just horrific because you can see life try to resume on this floodplain when it's drained for the four months it takes to clear. Little cypress seedlings start to sprout, which is encouraging because if they take the dam away it means the forest can come back and regrow. Springs start to bubble up in this period, and the original river channel is still there despite the reservoir overwhelming it. But this reservoir has been covering the natural landscape up for the past 50 years. Something needs to be done, in terms of political advocacy and change.

Q: On the topic of political advocacy, I'd like to discuss the political element of your exhibition. There's a wonderful duality to Structure of Nature | Nature of Structure it seems, as you simultaneously present a love letter to the beauty of our natural landscape and craft a call to action to preserve what little is left of it. What are you hoping viewers take away from this exhibition? What should they do to advocate for environmental conservation, or how should they begin learning to preserve these precious spaces?

A: There's two main ideas. First, we need to recognize that this beauty exists. It's there for us to witness and appreciate, and we need to realize that. I mean, to be able to go out into nature is a sort of therapy for me, and I think we all need to experience it. Don't deny yourself access to the natural world just because it's threatened. Explore the peace and solitude of these areas while they're still available.

Second, we need to be aware of the issues surrounding the environment and reconcile with the responsibility of awareness. I always try to include my own unawareness in the story, because I had to learn about these issues, and you can't be aware of everything that goes on that impacts the environment, but you can find the aspects of the issue that matter the most to you. If you're not the kind of person who writes letters to politicians and petitions and protests, that's okay, just support the organizations that are able to do those things. The Riverkeeper or North Florida Land Trust are good examples of local organizations that do a lot of good work here, and these small organizations need our support. So, whether it's a donation or volunteer work, do something.

Q: Could you briefly touch on how you take your photos? You mentioned briefly in your coverage of hurricane damage that you pull off main roads and highways with your tripod, but what other processes are involved to create such immersive photographs?

A: Accessibility is a big part of my photography. I want people to be able to go out and find these locations and witness their beauty in-person without going through a lot of effort. So, I don't really get up at four in the morning to go on a three hour hike with all of my camera gear on my back for a photo of the sunrise. I try to do a bit of planning, figuring out what roads are open and checking the weather, but if you get too into planning, you'll end up not doing anything. Lately I've been doing a lot of walking Huggins Creek and McCoy's Creek, I did that a lot over the summer. Those areas are city property so they're very accessible, you don't have to worry about being chased off because you accidentally wandered onto someone's private property, or fear getting run over on the edge of the interstate. But typically I drive or walk around with all of my camera gear and find a good location, unpack everything and take some pictures, pack it up and head onto the next spot. I don't work on particularly treacherous terrain, I like to use spaces that people can visit themselves if they feel compelled to after seeing my pictures.

View of Hogans Creek - East Monroe St. - upstream, from Eng's a new series on the urban creeks of Jacksonville.

Q: Are there any final thoughts or messages you would like to impart on viewers?

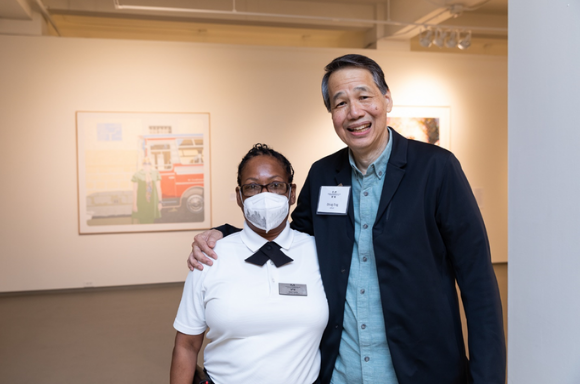

A: I really appreciate MOCA for allowing me to do the exhibition. It was something that I never thought I would be able to accomplish, you know, getting to put on a show in a contemporary art museum. So it's not only a surprise, it's a high honor and privilege to show my work to this audience. It's so rewarding to be able to see your work displayed that way. I could have never done an exhibition like this from my studio or done anything like what the museum has accomplished. I also have a great appreciation for the people working in the museum to make this possible, the staff members who have been so helpful and engaging.

There's so much value in the opportunities that museums provide, and a lot of times people don't even know that access to these learning opportunities exists. There needs to be more support for our cultural institutions, especially in Jacksonville. There are so many outlets for art and culture available here and no one knows about it. We have a blossoming art scene and so much to offer but it just isn't represented so no one knows to look for it. If I have a final message, it's to encourage everyone to take another look at Jacksonville, to put our museums and cultural institutions on your radar, because they exist and they're full of talent, but not enough people are seeing it. I want to encourage everyone to explore these parts of the city because you'll get something out of it, and I really hope my exhibition contributed to that in some way.

Artist Doug Eng and Chief of Security Sheri Verile at MOCA Jacksonville's opening for Nature of Structure | Structure of Nature, July 9, 2021.