KARA WALKER: CUT TO THE QUICK GALLERY GUIDE

>> © Kara Walker, African/American, edition 22/40, 1998. Linocut, 44 x 62 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 1998.53

COLLECTOR'S FOREWORD

I bought my first work by Kara Walker, The Keys to the Coop, back in 1997. The large linocut is nearly four feet tall and over five feet wide and features what appears to be a young African American girl about to devour the head of a chicken. I was completely mesmerized by this image, not only because it depicts such provocative subject matter on such a large scale, but also because of Kara Walker’s boldness and fearlessness in executing it. Since adding The Keys to the Coop to my collections, I have acquired over 125 works by Kara Walker, and I continue to be swept away by each new work of hers as her career has skyrocketed. Her work speaks to both the important history of African Americans and their struggle for equality as well as issues of racial and gender inequality, which are universal themes historically and continue to challenge society today.

I grew up in Portland, Oregon. When I was in the third grade, my mother opened the Fountain Gallery of Art, which focused on contemporary Pacific Northwest artists, so my love of art started at a young age. In the late 1980s, I began to buy prints and multiples by post–World War II American artists, and that collection now contains more than nineteen thousand works. The Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation’s exhibition program has traveled to over 160 museums in this country and abroad.

We previously toured Kara Walker’s work to eight museums and then let those objects rest for the last five years, so we were ready to showcase them to new audiences when we began speaking with the Frist Art Museum. In addition to thanking Susan Edwards, executive director and CEO, co-curator Ciona Rouse, and the entire staff of the Frist Art Museum, I am always appreciative of the work of Catherine Malone, our director of collections, and her team of nine hard-working staff—without them, the art would not make its way from our warehouse to world-class museums like the Frist!

I have often said that artists are chroniclers of their times. They force us to deal with issues that often are unpleasant but important—identity, power, and race. For me, waking up one day without art would be like waking up without the sun. Therefore, I would like to thank Kara Walker for creating art that grabs us and doesn’t let go until we face our values, our prejudices, and our stereotypes. I hope each viewer is as moved as I am by this exhibition and finds something that speaks to them from Kara Walker’s amazing work

— Jordan D. Schnitzer

>> © Kara Walker, The Keys to the Coop, edition 39/40, 1997. Linocut, 46 x 60 1/2 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 1997.15

CUT TO THE QUICK

This essay, written by Susan H. Edwards, PhD, is provided courtesy of the Frist Art Museum, Nashville.

Do you know what it means to have a wound that never heals?

— Natasha Trethewey

Kara Walker (b. 1969) is one of the leading visual artists of her generation, in part because of her prodigious talent in several mediums, but especially because she upends propriety with images of exaggerated stereotypes that address slavery, racism, exploitation, gender, and physical and sexual abuse. Walker is best known for her groundbreaking large-scale tableaux silhouettes, made using the cut-paper craft popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Her hard-hitting, unorthodox depictions of unspeakable subjects expose the raw flesh of generational wounds that have never healed.1

Kara Walker: Cut to the Quick, from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation includes works, created in various mediums between 1994 and 2019, that offer a broad overview of the artist’s career. The words of poet and exhibition co-curator Ciona Rouse included here coalesce genre within genre, expanding our understanding of the visual, verbal, oral, and performative complexity of Walker’s art.

Encountering a room-sized installation by Walker, one is struck by the drama of stark contrasts—black on white, and the reverse. Her art is less a study in opposites and more a panoply of ambiguity.

>>© Kara Walker, The Emancipation Approximation (Scene #25), edition 7/20, 1999–2000. Screenprint, 44 x 34 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2001.20y

The presentation of all twenty-seven black, white, and gray prints in the Emancipation Approximation series (1999–2000) offers a rare opportunity to see the artist’s riff on “emancipation,” or all that did not come with the promise of freedom. Walker alludes to the Greek myth of Leda and the Swan, in which the Olympic god Zeus takes the form of a swan to rape the human Leda—a subject tackled by artists from Leonardo da Vinci and Antonio da Correggio to Cy Twombly, as well as poets William Butler Yeats, Lucille Clifton, and Sylvia Plath. Sexual dominance, trickery, and subjugation reinforce dependency and intimidation while thwarting independence, courage, and ownership of one’s own body.

Throughout her career, Walker has been an avid student of history and literature, including novels like Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852) and Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind (1936)—the former vilifying slavery and the latter fueling the myth of the Lost Cause. She acknowledges that “I am not a historian. I’m an unreliable narrator.”2 She states:

I’m not making work about reality; I’m making work about images. I’m making work about fictions that have been handed down to me, and I’m interested in those fictions because I’m an artist, and any sort of attempt at getting at the truth of a thing, you kind of have to wade through these levels of fictions, and that’s where the work is coming from.3

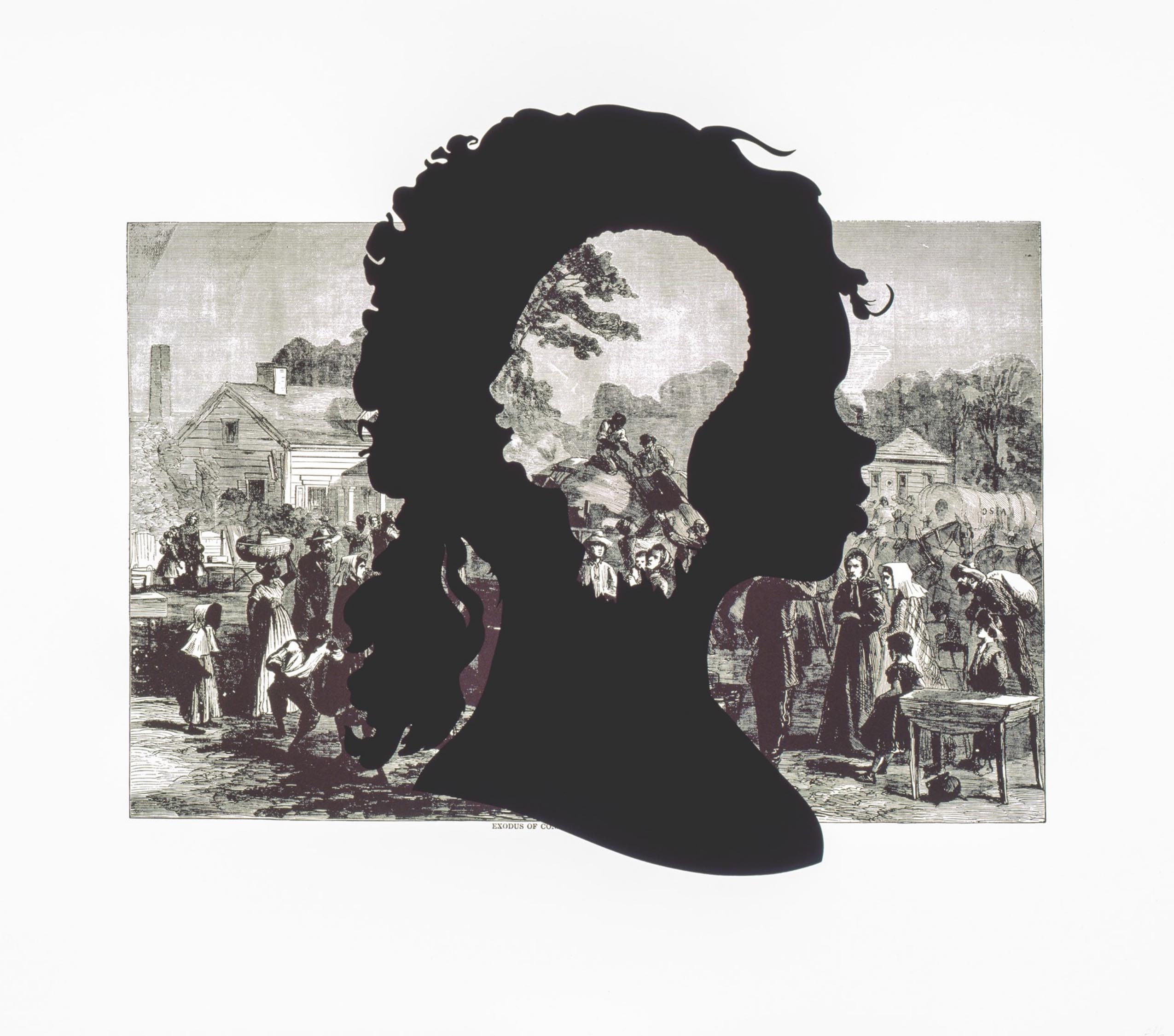

>> © Kara Walker, Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated): Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, edition 21/35, 2005. Offset lithography and screenprint, 39 x 53 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2005.339l

Between 1861 and 1865, Harper’s Weekly reported on Civil War battles and political developments, largely in support of Lincoln and the federal government. In 1894, the weekly published Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War by Alfred H. Guernsey and Henry M. Alden, with one thousand illustrations of battlefields, maps, plans, and likenesses of military figures. In 2005, Walker superimposed her signature silhouettes over large-scale prints from the pictorial history, annotating Harper’s contemporaneous account, which had been intentionally inoffensive to its Southern white readership. Walker’s flat, opaque forms insist that the African American point of view was conspicuously absent. Their deep negative space arrests the gaze and beckons the viewer into a black hole of spiraling emotions about the unreliability of history. Who is telling the story? Whose history is included, and whose is omitted? Who is validated, and who is obliterated?4

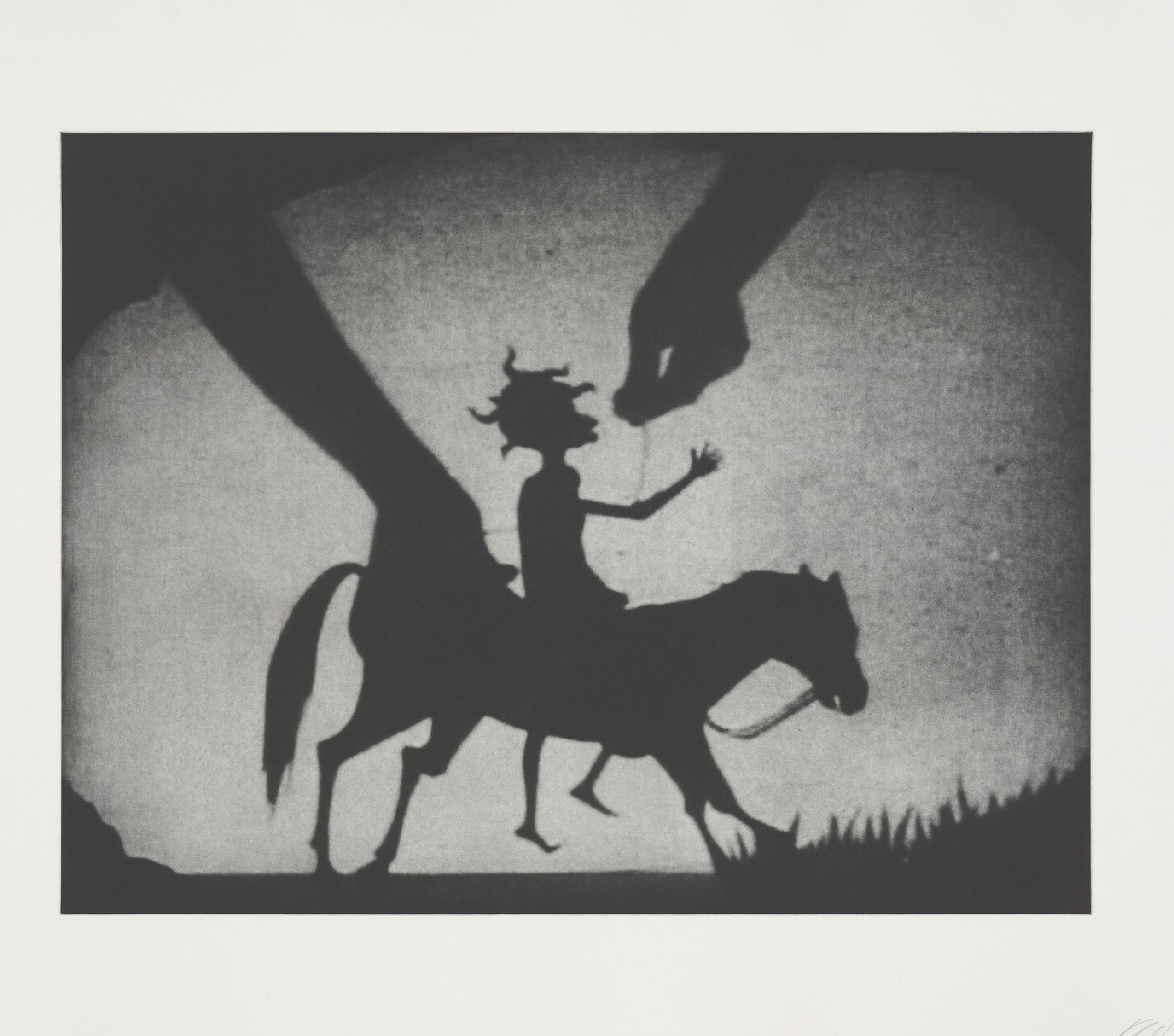

The Testimony suite (2005), five scenes from the video Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Fortune (2004), reveals the hand of the artist and the power of rudimentary production values. Walker’s physical presence among the shadow puppet reinforces an intentionality as potent as that of her precursors in social commentary: Honoré Daumier, Francisco Goya, Georg Grosz, and Käthe Kollwitz. Walker’s debt to the early twentieth-century animated films of Lotte Reiniger, long present in her silhouettes, is foregrounded in her photogravures and video art.

Mining the National Archives for War Department microfilm, Walker discovered the extensive records kept by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, which informed the subject matter of her 2009 video Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road.5 The bureau operated from 1865 until 1872, to assist those doing family and community research on the period following the Civil War and during Reconstruction. Precise records were maintained on disgraceful acts. Walker’s video, part history and part fiction, begins with a Black family engaged in daily chores, but soon the narrative switches to violence. Walker does not conceal her presence, but rather claims authorship by manipulating the figures and exposing the behind-the-scenes mechanics of production. Following the murder of the male protagonist, the burning of the family home is communicated through red and orange pieces of Mylar that flicker like flames to the chilling sound of sizzling bacon or fatback. This audio effect may be a reference to the meager diet of some rural Americans, or an allusion to branding and other forms of torture using fire and heat. A rape inflicts the final degradation.

>> © Kara Walker, Testimony, edition 12/14, 2005. Photogravure, 22 3/8 x 31 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2010.113b

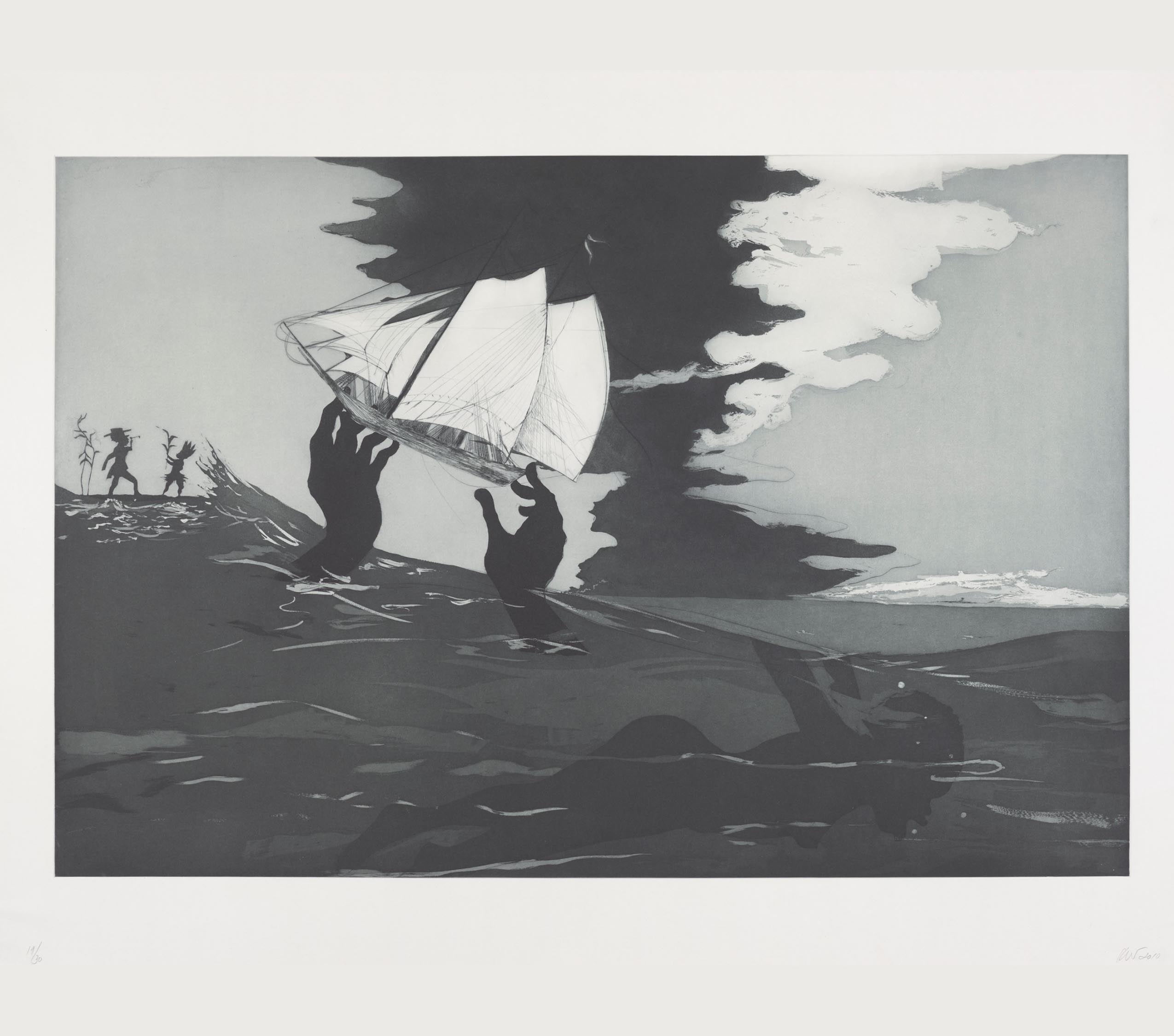

In 2010, Walker created a fictionalized account of the Middle Passage in An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters. Combining aquatint, sugar lift, spitbite, and drypoint etching techniques, Walker created the series of six prints to address the brutality of the transatlantic slave trade and its legacy, as well as the magical thinking of captives dreaming of flying or swimming back to Africa and freedom. In this body of work, the artist who claims to have “an uneasy relationship with my own imagination” takes poetic license with scale and proportion to weave a heartbreakingly plausible yet improbable two-dimensional and monochromatic tale.6

Set in 1920s Charleston, South Carolina, to music by George Gershwin, with a libretto by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin, the opera Porgy and Bess tells the story of two Black protagonists—Bess, the beautiful mistress of a man who manipulates her with drugs and money, and Porgy, a disabled beggar who loves her. The tragedy was criticized almost from the beginning for its characterization of the lifestyle of African Americans, as well as its use of their dialect, as imagined by white authors. When Alicia Hall Moran was cast as Bess in a 2011 production, she invited Walker to rehearsals. Walker made sketches as she watched “to understand the music and to allow myself to get caught up in the fantasy of theater.” The producers requested that she not use the drawings for salable work.7

>> © Kara Walker, An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters: no world, edition 19/30, 2010. Etching with aquatint, sugar lift, spitbite, and drypoint, 27 x 39 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2011.114a

Subsequently, Walker was approached by Arion Press to illustrate their publication of the opera’s lyrics. Bound by her promise, Walker created sixteen original lithographs for the book (2013), plus four lithographs for a companion portfolio, employing a loose, open style in contrast to her customary hard-edged images.8 The smudges, rubbings, and loose, broad strokes that lithography is well suited to reproducing are visually appropriate for the tender love story; like her drawings and early paintings the prints contain a handmade quality and intimacy that confirm the visceral presence of the artist.9 In a statement for the book, Walker says of the characters, “They’ve become archetypes of another no less grand drama, that of: ‘American Negroes’ drawn up by white authors, and retooled by individual actors, amid charges of racism, and counter charges of high-art on stage and screen, in the face of social and political upheaval, over generations.”10

In 2017, Kara Walker was invited to participate in Prospect.4, the New Orleans citywide triennial of contemporary art. She selected Algiers Point for a site-specific installation of a calliope mounted on a wagon. The organ-like musical instrument was reminiscent of nineteenth-century riverboats, as well as the steam engine, the cotton gin, and other inventions of the Industrial Revolution era. Walker commissioned American jazz pianist Jason Moran to compose and perform songs and sounds inspired by African American anthems of protest and celebration. The title Katastwóf Karavan, taken from the Haitian Creole word for “catastrophe,” refers to the life of subjugation, violence, and humiliation African captives endured before and after passing through the holding center located at Algiers Point. All four sides of the wagon and the maquette (small model) for the calliope in the exhibition feature scenes of the old South in Walker’s silhouette style, laser cut in stainless steel rather than paper. The reliefs recall the masterful shadowing and Afrocentric storytelling of visual artist Aaron Douglas that address social issues around race and segregation from the years of the Harlem Renaissance through Jim Crow and the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

>> © Kara Walker, The Katastwóf Karavan (maquette), edition 29/30, 2017. Painted laser-cut stainless steel, 9 1/8 x 14 5/8 x 5 1/2 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2017.486

The most recent work in the exhibition is Fons Americanus, a bronze replica of Walker’s now-demolished installation in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall.11 The original monument, over forty feet tall, was loosely based on the Victoria Memorial at Buckingham Palace, which had been erected in the early twentieth century in honor of the long-reigning queen; her attributes of constancy, courage, motherhood, justice, and truth; and implicitly the power, wealth, reach, and influence of England at the height of its imperialist domination.

Walker describes Fons Americanus as “a piece about oceans and seas traversed fatally. It is an allegory of the Black Atlantic and the global waters which disastrously connect Africa to America, Europe and economic prosperity.”12 With water as the foundational motif, Walker devised an interconnected flow of figures and scenes satirizing the pride of empire, condemning the violence and complicity of governments and private enterprise in constructing the transatlantic slave trade and perpetuating its legacies. The hand of the artist smears and drags across recognizable figures and scenes—an Afro-Caribbean Venus, seafarers, a tree with a hangman’s noose, the scales of justice—to articulate and obfuscate our messy reality. With a touch reminiscent of Auguste Rodin or Medardo Rosso, Walker provides haptic surfaces with spontaneity and unfettered élan.

>> © Kara Walker, Fons Americanus, edition 9/30, 2019. Bronze, 20 x 16 x 16 in. Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, 2020.111

The monument movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries placed memorials to the Civil War and various military figures throughout the United States, with over 1,500 in the South. Although many have been removed recently, over three hundred remain in Georgia alone, the state where Kara Walker lived with her family from age thirteen until she left for graduate school at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1991.13 Her poignant take on monuments predates the current wave of revisionist thinking about them, supporting the argument that her art continues to ask and answer the question, Can provoking discomfort, disgust, tension, and anxiety explode stereo-types and set us on a more equitable and just path?

In every visual medium, Walker continues to mine history, literature, mythology, art, culture, and personal experience for evidence of trauma and underlying, unrelenting, and unresolved pain. With each project, she unearths human complacency and complicity with no pity, patience, or sentimentality. She provokes self-examination and holds society accountable.

Her messages resound with added currency and urgency in the context of international reckoning with race. Sometimes it is hard to look carefully at Walker’s art because of how deeply she cuts and how she exposes collective culpability and shame. Still, we cannot retreat. She never does.

Susan H. Edwards, PhD

Frist Art Museum former executive director and CEO

Co-curator

NOTES

Epigraph. Natasha Trethewey, Memorial Drive: A Daughter's Memoir (New York: HarperCollins, 2020), 3.- Kim Wickham, “'I undo you, Master': Uncomfortable Encounters in the Work of Kara Walker,” Comparatist 39 (October 2015): 335-54.

- Tate, “Artist Kara Walker-'I'm an Unreliable Narrator,'” October 25, 2019, video on Fons Americanus, 5:58, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tV_L3fceGNA.

- Kara Walker, interview by Farai Chideya, “Kara Walker Rattles Art World Again,” NPR News & Notes, March 7, 2008, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=87985217.

- In 2012, Walker wrote “The Sweet Smell of Success and the Stench of Ingratitude . . . A Black Hole Is Everything a Star Longs to Be” across a long paper scroll. See “The Black (W)hole and What It Means to Me,” in Kara Walker: A Black Hole Is Everything a Star Longs to Be, edited by Anita Haldemann (Geneva: JRP, 2021), 222-23, 558-59.

- The full title of the video is National Archives Microfilm Publication M999 Roll 34: Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands: Six Miles from Springfield on the Franklin Road.

- SFMOMA, “An interview with Kara Walker,” Smarthistory, December 21, 2020, https://smarthistory.org/an-interview-with-kara-walker.

- Emily Nathan, “Kara Walker's Porgy & Bess Libretto,” ARTnews, March 19, 2014, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/kara-walker-creates-porgy-and-bess-libretto-2393/amp/.

- Ibid.

- Maurice Berger, “The Site of Memory: Kara Walker Drawing,” in Haldemann, Kara Walker, 574-85. Early in her career, Walker was drawn to nineteenth-century history paintings and how their grand scale created a powerfully immersive impact. She was also inspired by how James Ensor's subversive carnivalesque narratives effectively critiqued society by merging aspects of expressionism, symbolism, and surrealism.

- Ira Gershwin and DuBose Heyward, Porgy & Bess, with sixteen lithographs by Kara Walker (San Francisco: Arion Press, 2013).

- Fons Americanus was dismantled and demolished in 2020. The forty-three-foot-tall sculpture had been commissioned as a temporary installation. Likewise, A Subtlety, a seventy-five-foot-tall, sphinxlike sculpture made of sugar, had been commissioned by Creative Time for display at the former Domino Sugar Factory storage shed and was destroyed in 2014. Both installations were photographed extensively and documented on film for posterity.

- Tate, “Artist Kara Walker.”

- Walker lived the first thirteen years of her life in Stockton, California, where she was born in 1969. Her father, Larry Walker, moved the family to Atlanta in 1983, when he became a professor and director of the art program at Georgia State University, teaching there until his retirement in 2000.

THREE POEMS BY CIONA ROUSE

SILHOUETTE

Long long ago (& also not really so), a girl leapt in hopes she might step down into her shadow. Stand inside the black hole of her body. Let mystery hold her more tender than anything illuminated. But then her toes betray. No matter which way you chase a shadow, doesn't it always keep itself one step ahead? Is that why you stalk it? Sometimes she feels darkest when she lets you light her face and trace it. Ride her coastline, her curls and waves. Touch the tip of her nose, her lips and nape. Her nipples, her knees, her hills like dark high notes. Touch her deep bass. But no more hands on her body this time. Only her silhouette. A story begins & middles & ends. And even though it starts before the thought of you, it still casts itself against all your old-fangled names. All of your mothers' pains. Sometimes I feel darkest when I shine my own face and trace it and cut to the quick of my understanding. Whatever you assigned to darkest, leave it. Whatever to body, forget. And touch & leaping. Why don't you cut that, too?

Plunge into her true

silhouettes. They may pluck your neck.

Et la tête. O-o-oh.

BIRD OF FREEDOM / WHEREAS THE NEGRESS CAN FLY

Eenie-meenie-miney-mo. This woman's body is not her own. Even her shadows belong in part to the sun. If she hollers, he holds her mouth. If she opens her truth, he shuts her down. He centers himself in the crux of her diaphragm and plucks the feathers about to emerge from her spine. She learns it with his alphabet: A. B. C your body is not your own. 1. 2. 3. 4 generation after generation, too many not released from the heft of slavery. All of these masters stand, not ashamed of when they put their hands in her body. Not ashamed of how they force their bodies in her hands. What if she squeezed a bit harder? What if she bit into their hardness? What if every not got emancipated to now? Whereas he stands now ashamed. Whereas the crushing weight of slavery is now untethered to her progeny. Whereas her body is now her own. What if a body was never owned? Whereas on the first day all persons shall then be, shall be then forever free.

A swallow only knows

Wings wild, unfettered & flapping

She swallows him whole

THE SLAVE SHIP GETS NOWHERE WITHOUT THE SEA TO CARRY IT*

Once upon a now you motion still, perilous and inviting. You wave. You slide upon shore and shingle, with your foam inching toward my toes. Will you bite or sting or send me something more serene? With you, I never know. Are you witness? Are you accomplice? Are you forgiven? Come high days of humility, and you simply wash my pits. Come high days of holy, and you baptize my forehead. Come days of your wrath and whip, you flatten my cities. Come days of commerce and cargo, you hold a ship. And once upon a then you held bodies in the bosom of a ship until they leapt. And you swallowed them down. Drowned: these bodies unwanting to be owned. I said, you carry a heavy vessel but pin a body down. Yet word around town is you are life, sustaining and satiating all that I eat and breathe and be. And every sea in me shifts with the moon of memory. Ancient griefs still haunt me, propel me, lift me so that no body can let me down. Call me Venus or call me by name, however you see me, see me free. See these hands, these wrists unroped. See how I'm born, what I've borne, how I re-live again and again. Get closer to what pours out from me, open your mouth.

*The title is borrowed from Kara Walker's notes.